Let me reiterate that I don't by any stretch of the imagination consider myself as an authority on the text. I'm doing this to aid my own ongoing study and hopefully helping some other people at the same time.

Dogen is notoriously difficult to interpret for a number of reasons:

- As with all Zen Masters he is attempting to indicate something which cannot really be defined by words or even thoughts

- He uses ideas which are difficult and subtle

- His statements contradict one another - even from one sentence to the next. I would suggest that the key to understanding these contradictions lies in understanding that Buddhism teaches two truths - conventional truth and what is called 'ultimate' truth and the same situation can be described in contradictory terms from these two viewpoints.

- He writes in extended poetic metaphors, the meaning of which are not only difficult to grasp, but sometimes can only be understood as references to imagery used by his contemporaries and antecedents but which are now obscure

The Genjo Koan is widely regarded as being one of the key passages of the Shobogenzo and is probably the most widely discussed. No doubt my clumsy attempts to grasp the meaning will lose the poetic qualities of the text.

Being able to understand Dogen's writing does not mean one is 'enlightened'. And being unable to understand it does not mean that one lacks understanding of Buddhism. However, I hope that after this little project I will be in a better position to tackle the rest of the Shobogenzo. Hopefull it will be useful to others too.

The following lectures by Rev. Shohaku Okumura have been invaluable resources for me:

Dogen Zenji's Genjo-Koan Lecture

Genjo-Koan: Actualization of Reality, Part 2

And this is a very useful tool for comparing various translations:

8 English Translations of Genjokoan

As all things are buddha-dharma, there are delusion, realization, practice, birth and death, buddhas and sentient beings. As myriad things are without an abiding self, there is no delusion, no realization, no buddha, no sentient being, no birth and death. The buddha way, in essence, is leaping clear of abundance and lack; thus there are birth and death, delusion and realization, sentient beings and buddhas. Yet in attachment blossoms fall, and in aversion weeds spread.

There are two truths of Buddhism. The traditional teaching as originally described by Gautama Buddha is the conventional truth of Buddhism: delusion and enlightenment and the path from one to the other, life and death, ordinary beings and Buddhas. However when Right View is understood it is seen that all things are inter-dependent and have no fixed self - it is seen that is they have no ultimate existence, they are empty and thus never come into or pass out of existence. This is the second truth of Buddhism - it cannot be said that these entities exist, nor can it be said that they lack existence. Yet the actual practice of Buddhism goes beyond or is a middle path between these two conceptual truths of multiplicity and emptiness. This corresponds to the third truth of Buddhism according to the Tien T'ai/Tendai sect. It is because things are empty, because there are no fixed natures that change and being are possible, hence there is birth and death, delusion and enlightenment, Buddhas and ordinary beings as we experience them. However, it is desire and aversion to all such unsubstantial phenomena of all sorts which is the root of our suffering.

To carry the self forward and illuminate myriad things is delusion. That myriad things come forth and illuminate the self is awakening.

Those who have great realization of delusion are buddhas; those who are greatly deluded about realization are sentient beings. Further, there are those who continue realizing beyond realization, who are in delusion throughout delusion. When buddhas are truly buddhas, they do not necessarily notice that they are buddhas. However, they are actualized buddhas, who go on actualizing buddha.

Buddhist practice which is self-centred, that is it is, seen as an attempt to reach enlightenment through the efforts of the individual self, is based on the delusion of fixed-self. Practice which is seen as the expression of all things through the individual self is the enlightened view. To see delusion as delusion is enlightenment; to be deluded about enlightenment (to see it as separate from the reality of here and now for example) is samsara. Some are awakened about awakening and some are deluded about delusion. Being a Buddha (being a non-conceptual realisation) does not necessarily mean that one knows one is Buddha, but being a Buddha is a process of ongoing, unfolding awakening.

When you see forms or hear sounds, fully engaging body-and-mind, you intuit dharma intimately. Unlike things and their reflections in the mirror, and unlike the moon and its reflection in the water, when one side is illumined, the other side is dark.

Through absorption of our whole being into phenomena, we know phenomena intimately, but to see this as a duality - the mind reflecting phenomena like a mirror is an error. We cannot see the objective and our subjective perception of it side by side, because there is only one reality.

To study the buddha way is to study the self. To study the self is to forget the self. To forget the self is to be actualized by myriad things. When actualized by myriad things, your body and mind as well as the bodies and minds of others drop away. No trace of realization remains, and this no-trace continues endlessly. When you first seek dharma, you imagine you are far away from its environs. At the moment when dharma is correctly transmitted, you are immediately your original self.

Buddhist practice is the study of the self. Studying the self, we realise that there is no fixed self, that the self is empty. To realise this is to realise ourselves as an expression of all reality. When this occurs, all sense of our own self and that of others as actual separate identities disappears. All attachment to concepts drops away - even the thought of our own realisation - we become free from such conceptual attachments. When you first seek Awakening you imagine that you are far from it, but when you attain it, you realise it is what you already are.

When you ride in a boat and watch the shore, you might assume that the shore is moving. But when you keep your eyes closely on the boat, you can see that the boat moves. Similarly, if you examine myriad things with a confused body and mind you might suppose that your mind and nature are permanent. When you practice intimately and return to where you are, it will be clear that nothing at all has unchanging self.

Our perspective on the universe is distorted by the fact of our subjectivity - that part of that which is being observed is that which is doing the observing. Because our mind cannot really see itself we imagine that it remains constant while the reality around it changes. But through Buddhist practice we can realise that nothing has a fixed self, nothing remains unchanged.

Firewood becomes ash, and it does not become firewood again. Yet, do not suppose that the ash is after and the firewood before. You should understand that firewood abides in the phenomenal expression of firewood, which fully includes before and after and is independent of before and after. Ash abides in the phenomenal expression of ash, which fully includes before and after. Just as firewood does not become firewood again after it is ash, you do not return to birth after death.

This being so, it is an established way in buddha-dharma to deny that birth turns into death. Accordingly, birth is understood as no-birth. It is an unshakable teaching in the Buddha's discourse that death does not turn into birth. Accordingly, death is understood as no-death.

Birth is an expression complete this moment. Death is an expression complete this moment. They are like winter and spring. You do not call winter the beginning of spring, nor summer the end of spring.

Because entities lack a fixed self, change is possible and irreversible. In the process of change it is a mistake to see an earlier state and a later state as earlier and later states of one continuous entity. Each state or moment both includes its past and future and is free from it at the same time. The past and future of each state exists, but they exist in that moment. Each state is just itself. Just as a phenomenon does not return from a later stage to an earlier stage, death does not become life. There is no continuous identity (ie. atman) that survives from one life into another.

That birth does not become death, that there is no fixed self that continues from birth to death is accepted Buddhist doctrine. Because of this birth is not the real beginning of a real continuous entity - birth is unborn... It is also taught that there is no fixed self that continues from death to birth. Because there is no continuous self to come to an end, the true understanding of death is 'no death'...

Birth and death are not the birth and death of an imagined additional continous entity - the fixed self. Birth and death are just fully the reality of themselves at the time when they exist and no more. There is no fixed entity that comes into being or stops being, there is just endless unfolding change.

Enlightenment is like the moon reflected on the water. The moon does not get wet, nor is the water broken. Although its light is wide and great, the moon is reflected even in a puddle an inch wide. The whole moon and the entire sky are reflected in dewdrops on the grass, or even in one drop of water.

Enlightenment does not divide you, just as the moon does not break the water. You cannot hinder enlightenment, just as a drop of water does not hinder the moon in the sky. The depth of the drop is the height of the moon. Each reflection, however long or short its duration, manifests the vastness of the dewdrop, and realizes the limitlessness of the moonlight in the sky.

When we Awaken we realise that reality is expressed through us, like the moon reflected in water. The whole of reality expresses itself in each and every part of reality. Yet the vastness of reality does not affect our being and our enlightenment does not interfere with the universe. Reality is exactly itself whether we realise its true nature or not.

When dharma does not fill your whole body and mind, you think it is already sufficient. When dharma fills your body and mind, you understand that something is missing. For example, when you sail out in a boat to the middle of an ocean where no land is in sight, and view the four directions, the ocean looks circular, and does not look any other way. But the ocean is neither round nor square; its features are infinite in variety. It is like a palace. It is like a jewel. It only looks circular as far as you can see at that time. All things are like this.

Though there are many features in the dusty world and the world beyond conditions, you see and understand only what your eye of practice can reach. In order to learn the nature of the myriad things, you must know that although they may look round or square, the other features of oceans and mountains are infinite in variety; whole worlds are there. It is so not only around you, but also directly beneath your feet, or in a drop of water.

People who have a partial realisation of Buddhism think that they have the whole teaching. When you are fully awakened you can see the limitation of your own perspectives. To realise the 'oneness' of all things is not complete awakening, because our point of view is always limited, even our sense of oneness. In actuality, reality has infinite appearances and 'oneness' is just one of them.

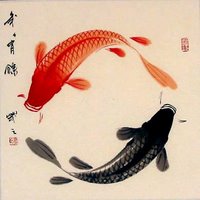

A fish swims in the ocean, and no matter how far it swims there is no end to the water. A bird flies in the sky, and no matter how far it flies there is no end to the air. However, the fish and the bird have never left their elements. When their activity is large their field is large. When their need is small their field is small. Thus, each of them totally covers its full range, and each of them totally experiences its realm. If the bird leaves the air it will die at once. If the fish leaves the water it will die at once.

Know that water is life and air is life. The bird is life and the fish is life. Life must be the bird and life must be the fish. You can go further. There is practice-enlightenment which encompasses limited and unlimited life.

The fish in the water and the bird in the air are metaphors for sentient beings in emptiness, in the dharma, in reality, fully at one with the dharma, inseparable from it, unable to leave it, yet unconscious of it.

Now if a bird or a fish tries to reach the end of its element before moving in it, this bird or this fish will not find its way or or its place. When you find your place where you are, practice occurs, actualizing the fundamental point. When you find your way at this moment, practice occurs, actualizing the fundamental point; for the place, the way, is neither large nor small, neither yours nor others'. The place, the way, has not carried over from the past, and it is not merely arising now.

This is Dogen's conclusion as to how we should live according to the Buddha Dharma. We should not conceptually try to investigate all of reality before we allow ourselves to live in it. To practice Buddhism is to find your place in reality - it makes reality real, rather than conceptual. This place is not far away - it can be found right where you are. Finding your place is something that occurs only at the present moment and awakening is something that occurs only at the present moment. This place does not belong to self or non-self; it is neither true to say that it has existed eternally nor is it just coming into existence. (All of these ways of thinking about it would be to ascribe to it a separate essence or self and thus lose it.)

Accordingly, in the practice-enlightenment of the buddha way, to attain one thing is to penetrate one thing; to meet one practice is to sustain one practice.

Here is the place; here the way unfolds. The boundary of realization is not distinct, for the realization comes forth simultaneously with the mastery of buddha-dharma. Do not suppose that what you realize becomes your knowledge and is grasped by your intellect. Although actualized immediately, the inconceivable may not be apparent. Its appearance is beyond your knowledge.

'To penetrate' here means 'to be be absorbed into', 'to lose all sense of separation from'. Correct Buddhist practice is to do whatever it is that we are doing with all of our being - not necessarily with all of our 'effort' (if such a thing has meaning here) but with all of our being, so that there is no distinction between us and the phenomenal reality of our actions, whether that be kinhin, zazen, eating, working or whatever. Because realisation occurs at the same time as our self 'becomes one with all things' there is no clear moment of self-awareness of enlightenment. Realisation is not conceptual knowledge and when it appears we cannot really know it intellectually.

Mayu, Zen master Baoche, was fanning himself. A monk approached and said, “Master, the nature of wind is permanent and there is no place it does not reach. Why, then, do you fan yourself?”

“Although you understand that the nature of the wind is permanent,” Mayu replied, “you do not understand the meaning of its reaching everywhere.”

“What is the meaning of its reaching everywhere?” asked the monk again. Mayu just kept fanning himself. The monk bowed deeply.

The actualization of the buddha-dharma, the vital path of its correct transmission, is like this. If you say that you do not need to fan yourself because the nature of wind is permanent and you can have wind without fanning, you will understand neither permanence nor the nature of wind. The nature of wind is permanent. Because of that, the wind of the buddha's house brings forth the gold of the earth and makes fragrant the cream of the long river.

This koan is a metaphor for Dogen's 'Great Doubt' - if we are already enlightened then why do we need to practice? The wind is the wind of dharma, reality, suchness. Fanning the wind represents Buddhist practice ie. Zazen. If the dharma is permanent and reaches everywhere why do we need to make any effort? The dharma does reach everywhere but delusion obscures it. The dharma fully penetrates even delusion, hatred and attachment. Yet those things are still confuse our mind. Practice eliminates these things allowing us to realise our own oneness with the dharma - our own original enlightenment allowing us to be free to be happy.